Sask Polytech helps to solve blind hockey's biggest riddle

While the sport of blind hockey has been around since the 1950s, the question of what to use as a puck has, until very recently, remained the unsolved Rubik's Cube of the game.

Played by athletes with 10 per cent vision or less, the game uses an adapted puck that is bigger and slower, and makes noise on the ice. Variations that have been tried include a nail-embedded plastic wheel from a toy wagon, a juice can and a sheet-metal puck filled with ball bearings—capable of doing considerable damage.

But now, thanks to the efforts of a six-person team in the Electronics Systems Engineering Technology program at Sask Polytech, a new puck is being developed around which the blind hockey community can build the sport—and perhaps one day take it to the Paralympics.

It all started when Mike Simmonds, a blind hockey player who lost his sight due to diabetic retinopathy, approached Anthony Voykin at the Saskatoon campus to discuss a solution.

‘SO FAR ADVANCED'

Simmonds is the only Saskatchewan player participating in an annual international tournament held by Courage Canada Hockey for the Blind, a national charity that leads the development of the sport.

"We were more than willing to support such a neat project that improves the quality of life of those with vision impairment," Voykin says. He approached the polytechnic's applied research office to secure more than $20,000 in funding.

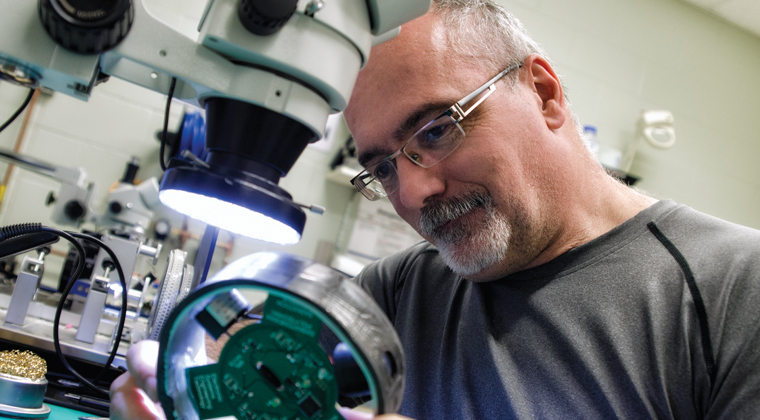

Voykin's team came up with the idea of a puck that is rubberized on the outside, with a familiar look and feel, although larger at five inches in diameter as opposed to a regulation puck's three inches. Inside are the protected electronics that make it beep and vibrate so that players can hear it when it's flying through the air.

When the stick hits it, the pulses of sound speed up. The final electronic prototype was used on the ice at the Courage Canada tournament in Toronto in February.

"The players told us the puck is so far advanced from anything they've used in the past. The executive director of Courage Canada told us they're certainly in it for the long haul to make this puck as accessible as possible," Voykin says.

Simmonds, a comedian and writer who often works blind hockey into his routine, could not be more pleased.

"Everybody I spoke with at the tournament was really excited to hear that we've got a school taking the time to design something, get players' feedback and actually get it right," he says.

"There have been close to 70 puck attempts so far. This one looks like it's on the right track for sure."